Landsvirkjun and Century Aluminum agree on new power tariff

A new power contract between Landsvirkjun and the Norðurál smelter of Century Aluminum at Grundartangi in Iceland, was negotiated in 2016. Landsvirkjun describes this contract as an extension of the original contract from 1997. That original contract was amended in 1999, extending the validity of the original power contract to 2019.

The new extension, concluded in May 2016, changes the terms of the older contract and will enter into force in 2019. This is a fairly short-time contract/extension, expiring already in 2023. This short time frame of the contract is interesting, as all the earlier Icelandic power contracts with aluminum smelters in Iceland have applied for much longer periods (usually from 20 to 40 years).

The new extension, concluded in May 2016, changes the terms of the older contract and will enter into force in 2019. This is a fairly short-time contract/extension, expiring already in 2023. This short time frame of the contract is interesting, as all the earlier Icelandic power contracts with aluminum smelters in Iceland have applied for much longer periods (usually from 20 to 40 years).

The new contract-terms include a major change of the pricing method for energy delivered to Norðurál. From 2019, the tariff will be linked to the market price for power in the Nordic power market (Nord Pool Spot; NPS). This replaces the previous price-link to aluminum prices at the London Metal Exchange (LME), which is used in the current power contract from 1997/1999.

According to the EFTA Surveillance Authority (ESA), the electricity tariff in the new contract is “tied” to the monthly “market price for power in the Nordpool Elspot power market”. This clear reference to Elspot may not necessarily mean that the new price will be exactly the same as the spot market power price on NPS. However, it is clear that this new pricing method, replacing the previous/current price-link to aluminium price, will make the revenues of Landsvirkjun more aligned with power prices on the Nordic and European power markets. What is also new, is that this being the first power contract with an aluminum smelter in Iceland not having the transmission cost included. Norðurál will need to pay the transmission cost directly to the Icelandic TSO; Landsnet.

Linking the power tariff to electricity prices abroad is a new approach in the pricing of Icelandic electricity to aluminum smelters. This new approach is a clear sign of important changes in the Icelandic power market, moving towards the development on nearby power markets in NW-Europe. The result will probably be a doubling of the current power tariff to the Norðurál smelter, when the new extension comes into effect in 2019 (depending on price development in the Nordic power market).

Linking the power tariff to electricity prices abroad is a new approach in the pricing of Icelandic electricity to aluminum smelters. This new approach is a clear sign of important changes in the Icelandic power market, moving towards the development on nearby power markets in NW-Europe. The result will probably be a doubling of the current power tariff to the Norðurál smelter, when the new extension comes into effect in 2019 (depending on price development in the Nordic power market).

The new pricing method may explain why the contract was only made for a four-year period (2019-2023). When negotiations between Landsvirkjun and Norðurál were ongoing, in 2015 and early 2016, the Elspot power price at NPS was very low (close to 21 EUR/MWh on average in 2015). The management of Norðurál most likely pushed for aligning the power tariff to the then current low electricity price in NW-Europe and/or N-America, in the hope of avoiding a higher tariff, like Landsvirkjun agreed with the ISAL smelter in 2010. The ISAL smelter in Straumsvík, owned by Rio Tinto, is now paying more than 30 EUR/MWh and a little under 30 EUR when transmission cost is excluded.

Although NPS did experience very low power price in 2015, it is quite possible that the spot price on the Nordic power market will rise in the coming years. Already in 2016, the average Elspot price on NPS was close to 27 EUR/MWh (up from 21 EUR/MWh the year before). So it was obviously quite risky for Norðurál to make a long-term contract based on the Elspot price; thus agreeing on a four year contract only.

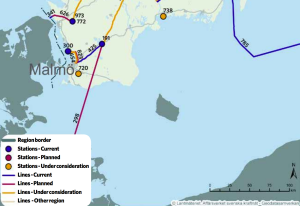

Landsvirkjun may also have wanted to avoid a new long-term contract, as the necessary power capacity is already available (no new investment in power generation is needed to deliver the power to the Norðurál smelter). The main reason for such a strategy of Landsvirkjun – going for a short-term contract – is the possible construction of an electric HVDC cable between Iceland and Britain (often referred to as IceLink).

Landsvirkjun may also have wanted to avoid a new long-term contract, as the necessary power capacity is already available (no new investment in power generation is needed to deliver the power to the Norðurál smelter). The main reason for such a strategy of Landsvirkjun – going for a short-term contract – is the possible construction of an electric HVDC cable between Iceland and Britain (often referred to as IceLink).

If such a subsea interconnector will be developed in the near future, it might become operational around 2025 or few years later. Such an interconnector would offer Landsvirkjun the opportunity to sell power into the high priced electricity market on the UK. Thus, a short time power contracts makes sense for Landsvirkjun, at this point, rather than making long-term commitments regarding electricity sales to aluminum smelters. This reflects the current strategy of the Norwegian power company Statkraft, which also is focusing on the spot market development rather than making new long-term power contracts.

We at the Icelandic and Northern Energy Portal will soon be analysing this new contract/extension of Landsvirkjun and Norðurál in more details, putting the new tariff into context with other new power contracts in Iceland and Canada. Stay tuned.