IceLink interconnector in operation by 2025?

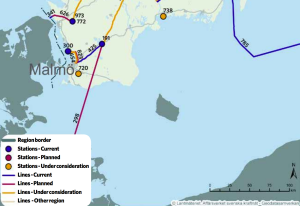

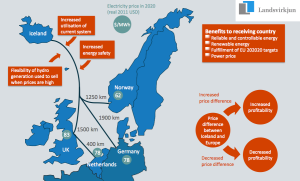

The proposed HVDC power interconnector between UK and Iceland, sometimes referred to as IceLink, seems to be moving along. This is happening despite the imminent Brexit and the uncertainty that the Brexit creates regarding Britain’s future energy policy.

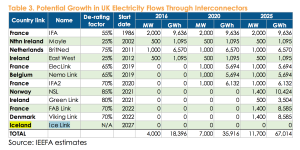

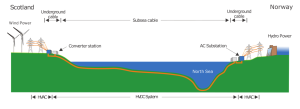

The British company Atlantic SuperConnection, which seems to be a subsidiary of Disruptive Capital Finance, has for years been introducing plans for a 1,200 MW subsea power cable between Britain and Iceland. About a year ago, Atlantic SuperConnection claimed the cable might be in operation already by 2023. Now the company says that the plan is to have the cable ready and operating in 2025. It is also interesting that Atlantic SuperConnection recently announced plans for constructing a factory in Northeastern England where the cable will be made. This new highly special cable-factory is supposed to be ready within a few years from now.

The British company Atlantic SuperConnection, which seems to be a subsidiary of Disruptive Capital Finance, has for years been introducing plans for a 1,200 MW subsea power cable between Britain and Iceland. About a year ago, Atlantic SuperConnection claimed the cable might be in operation already by 2023. Now the company says that the plan is to have the cable ready and operating in 2025. It is also interesting that Atlantic SuperConnection recently announced plans for constructing a factory in Northeastern England where the cable will be made. This new highly special cable-factory is supposed to be ready within a few years from now.

If these plans of Atlantic SuperConnection will be realised, the demand for Icelandic electricity will probably increase by many thousands of GWh annually, even as soon as in 2025. In this article we discuss these very ambitious (and somewhat unrealistic) plans of Atlantic SuperConnection.

No new power plant required?

As described later in the article, the required annual generation for the IceLink cable is estimated to be approximately 5,000-6,000 GWh. Current total electricity production and consumption in Iceland is about 19,000 GWh per year. It is interesting to examine how it will be possible to provide all the electricity needed for the IceLink cable.

Having regard to the current electricity production and consumption in Iceland at 19,000 GWh, it is interesting that on its website Atlantic SuperConnection says that it will be possible to have the IceLink operating even with “few or no new power plants” in Iceland. This statements by Atlantic SuperConnection is somewhat misleading, as it is obvious the IceLink will call for major construction of new (and upgraded) power plants in Iceland.

Having regard to the current electricity production and consumption in Iceland at 19,000 GWh, it is interesting that on its website Atlantic SuperConnection says that it will be possible to have the IceLink operating even with “few or no new power plants” in Iceland. This statements by Atlantic SuperConnection is somewhat misleading, as it is obvious the IceLink will call for major construction of new (and upgraded) power plants in Iceland.

Landsvirkjun’s view is very different from Atlantic SuperConnection

The view of Atlantic SuperConnection, introducing that there may be no need for any new power plant in Iceland, is in contrast to the vision that the Icelandic national power company Landsvirkjun has introduced regarding the cable. In a series of presentations and interviews Landsvirkjun’s management has said that the IceLink cable would need a supply of between 5,000-6,000 GWh. Landsvirkjun has also introduced that most of this electricity needs to come from new power plants. According to current information on the website of Landsvirkjun, the cable would export about 5,700 GWh and due to transmission losses in Iceland the cable will need a generation of close to 5,800 GWh. Here we should also have in mind that, according to estimates by Atlantic SuperConnection, the transmission losses in the subsea cable are expected to be close to 5%.

Electricity generation in Iceland must be increased by 30%

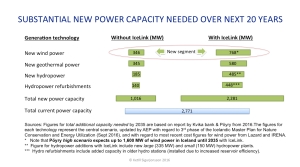

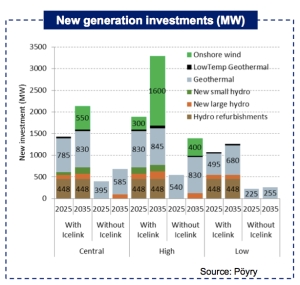

For a number of years Landsvirkjun’s scenario regarding power generation for the IceLink was as follows:

- Total additional generation in Iceland for the cable was expected to be 5,000 GWh annually.

- 2,000 GWh would be achieved by better utilization of the existing power system in Iceland, including utilisation of current over-flow in the hydropower plants, and by putting up new turbines in existing hydroelectric power plants (including 150 MW in the Kárahnjúkar power station).

- 3,000 GWh would be achieved by constructing new power plants in Iceland, including both geothermal, hydro and wind power.

Landsvirkjun has now increased these figures and now assumes the following:

- Total generation in Iceland for the IceLink cable is now expected to be 5,800 GWh annually.

- 1,900 GWh would be achieved by better utilization of existing power system in Iceland, including new turbines in existing hydroelectric power plants and utilisation of hydro over-flow.

- 3,900 GWh would be achieved by constructing new power plants in Iceland, including both geothermal, hydro and wind power.

- This means that just to fulfill the power demand of the IceLink cable, it would be necessary to increase electricity production in Iceland from the current 19,000 GWh to approximately 24,800 GWh. Which is approximately 30% increase.

So the national power company of Iceland introduces that to have enough power available for IceLink, Iceland needs to increase its electricity generation by 30% and approximately 3,900 GWh of this will need to come from new power plants. At the same time, Atlantic SuperConnection says that “ideally” the IceLink will call for none or at et last few new power plants in Iceland. This statement by Atlantic SuperConnection is not realistic, and becomes even more puzzling when having regard to the fact that the figures from Landsvirkjun are based on the prerequisite that the IceLink will have a capacity of 1,000 MW. While Atlantic SuperConnection says the cable will be 1,200 MW.

So the national power company of Iceland introduces that to have enough power available for IceLink, Iceland needs to increase its electricity generation by 30% and approximately 3,900 GWh of this will need to come from new power plants. At the same time, Atlantic SuperConnection says that “ideally” the IceLink will call for none or at et last few new power plants in Iceland. This statement by Atlantic SuperConnection is not realistic, and becomes even more puzzling when having regard to the fact that the figures from Landsvirkjun are based on the prerequisite that the IceLink will have a capacity of 1,000 MW. While Atlantic SuperConnection says the cable will be 1,200 MW.

Discrepancy between Landsvirkjun and Atlantic SuperConnection

In fact several important aspects in the presentation of IceLink by Atlantic SuperConnection are at odds with facts and reality. And the difference between Landsvirkjun’s scenario and the claims made by Atlantic SuperConnection may even weaken the credibility of the IceLink project. Probably it would be advisable for Atlantic SuperConnection and Disruptive Capital to clarify or explain the inconsistency. In addition, Atlantic SuperConnection seems to misunderstand the energy situation in Iceland. On its website the company states that it can approach and ”bring a near-limitless source of clean hydroelectric and geothermal power to the UK”. This is far from the reality.

Solutions to consider

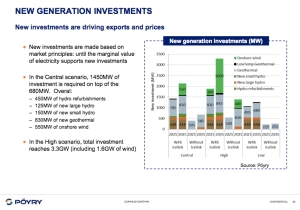

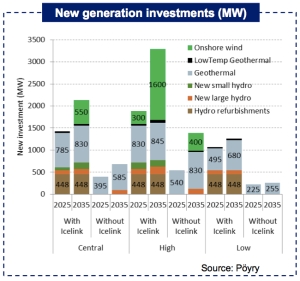

However, it is indeed possible to supply IceLink with enough green power from Iceland. There are roughly three options how to do this:

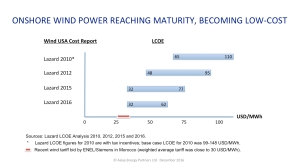

- By major construction of new geothermal-, hydro-, and wind power plants, in addition to major upgrading in current hydropower plants and utilisation of over-flow from current hydro reservoirs. This is the scenario which has been introduced by Landsvirkjun and is the most realistic way to develop the project.

- By utilizing the power that currently is consumed by the aluminum smelter of Norðurál (Century Aluminum). Most of the power contracts with the Norðurál smelter will run out in the period 2023-2026, which may fit the timeline for IceLink. However, this scenario would probably be met with heavy resistance from the communities close to the smelter, and is hardly a realistic option.

- By scaling the cable down to a maximum size of approximately 600-700 MW. Then the generation-need for the cable would probably be around 3,000-4,000 GWh. Although this size of cable would also call for substantial increase of power generation and construction of some new power stations in Iceland, it would make the project more manageable. The question remains if a cable of such a limited size would ever become economical.

If Atlantic SuperConnection really wants to see a power cable between Iceland and UK become a reality, the company should probably emphasise scenario no. 1 above (although scenario no. 3 may also be considered). This kind of project is indeed an interesting option for both countries; Iceland and Britain. Yet, it will never be realised unless it will be based on facts and the will and support of the Icelandic government.

If Atlantic SuperConnection really wants to see a power cable between Iceland and UK become a reality, the company should probably emphasise scenario no. 1 above (although scenario no. 3 may also be considered). This kind of project is indeed an interesting option for both countries; Iceland and Britain. Yet, it will never be realised unless it will be based on facts and the will and support of the Icelandic government.