Norwegians see high value in Icelandic wind

Sarpsborg, Norway and Reykjavík, Iceland.

Media release, May 7 2019.

The Norwegian wind power developer Zephyr has established a wind energy firm in Iceland; Zephyr Iceland. The company intends to invest considerable funds in research on Icelandic wind conditions, with the aim of constructing wind farms in the coming years, offering new type of renewable power at competitve prices.

The Norwegian wind power developer Zephyr has established a wind energy firm in Iceland; Zephyr Iceland. The company intends to invest considerable funds in research on Icelandic wind conditions, with the aim of constructing wind farms in the coming years, offering new type of renewable power at competitve prices.

Public Norwegian ownership

Norwegian Zephyr is owned by three Norwegian hydropower companies. They are Glitre Energi, Vardar, and Østfold Energi. These three companies are owned by Norwegian municipalities and counties. The projects of Zephyr Iceland will be managed by Ketill Sigurjónsson, who is also shareholder in the wind power firm. Ketill is the founder of Askja Energy Partners and chief editor of the Icelandic and Northern Energy Portal.

More than 500 MW of wind power in operation

In Norway, Zephyr has already constructed more than 300 MW of wind power capacity, representing an investment of more than ISK 35 billion. Having regard to current projects, the company will soon be operating close to 500 MW of wind power in Norway. This equals the electricity consumption of approximately 75.000 Norwegian households.

Major international customers

Zephyr not only possesses high level of technical knowledge of experience in all aspects of wind power development, but also has good relationships with major international investors and customers. Among Zephyr’s partners in its projects so far are technology giant Google, global investment management corporation Black Rock, and aluminum producer Alcoa.

Olav Rommetveit, CEO of Zephyr and Chairman of the board of Zephyr Iceland:

“Iceland has amazing wind resources. Even better than Norway. So I am very pleased with our decision in Zephyr to have Iceland as our first market outside Norway. Iceland’s excellent wind resources in combination with the strong flexibility of the Icelandic hydropower system creates exceptionally good opportunities to utilize the wind energy very efficiently.”

Morten de la Forest, member of the board of Zephyr Iceland:

“Zephyr has for some time carefully been studying the Icelandic power market and the relevant legislation and policies. Our company sees strong indications that Icelandic wind will be competitive with both hydropower and geothermal power, creating significant opportunities for Iceland to develop economical green wind power projects.”

Ketill Sigurjónsson, Managing Director of Zephyr Iceland:

“Having regard to Iceland´s strong winds it is about time to start utilizing the Icelandic wind resources for electricity production. This will contribute to an even stronger competitiveness of the Icelandic electricity sector. With an experienced and qualified partner as Norwegian Zephyr, Zephyr Iceland will have great possibilities to implement our vision for a new low-cost and environmental friendly type of green energy production. At Zephyr Iceland our focus will be on careful project preparation and good cooperation with all parties involved. Iceland’s future is windy and bright.”

For further information please contact Ketill Sigurjónsson, Managing Director of Zephyr Iceland, by sending message here.

The photo above shows the 160 MW Tellenes wind farm of Zephyr in Norway.

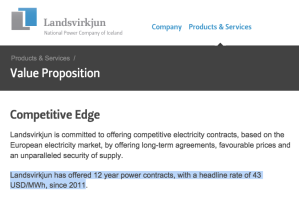

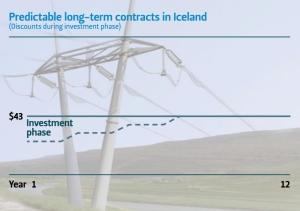

Landsvirkjun’s

Landsvirkjun’s