Rising power prices in Iceland

Electricity demand in Iceland is growing and most of the low-cost options in the geothermal- and hydropower sectors have already been harnessed. Thus, it is not surprising that wholesale electricity prices on the Icelandic power market have been rising. What is no less important for the Icelandic power sector, are the rising tariffs in special contracts with heavy industries in Iceland.

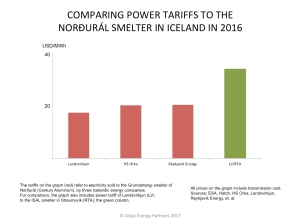

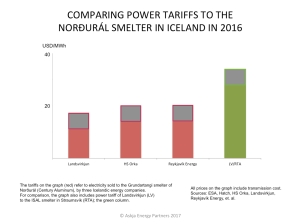

Heavy industries, like aluminum smelting, ferrosilicon production etc., consume close to 80% of all electricity generated in Iceland. The older power contracts with heavy industries offer the industrial companies the electricity at very low price. The chart at left shows the industrial tariffs in Iceland in 2016 (average tariff through the year). Note that the tariffs shown include transmission cost. The most recent contract is of course the one with the RTA smelter, while the oldest contracts with Elkem and Century Aluminum where negotiated two decades ago.

Heavy industries, like aluminum smelting, ferrosilicon production etc., consume close to 80% of all electricity generated in Iceland. The older power contracts with heavy industries offer the industrial companies the electricity at very low price. The chart at left shows the industrial tariffs in Iceland in 2016 (average tariff through the year). Note that the tariffs shown include transmission cost. The most recent contract is of course the one with the RTA smelter, while the oldest contracts with Elkem and Century Aluminum where negotiated two decades ago.

It is likely that the average general industrial tariff in Iceland will rise in the coming years. Icelandic power firms are already in the process of increasing price of electricity to industries in Iceland. The contract between the national power company Landsvirkjun and the RTA smelter at Straumsvík in 2010 was the first real step in this development. In 2010, the tariff to RTA increased substantially and is no longer linked to price development of aluminum. Instead it aligns with the US Consumer Price Index (CPI).

Another important step in increasing revenues from electricity sales to heavy industries in Iceland was taken in 2016, with a new power contract of Landsvirkjun and the Norðurál smelter of Century Aluminum. This new contract will become effective in 2019. From then, the tariff to Norðurál will become aligned with spot price on the Nordic power market (Elspot on Nord Pool Spot). Landsvirkjun is also re-negotiating the power tariff with the ferrosilicon plant of Elkem, which has been paying very low price for the electricity. The expected power price Century and Elkem will be paying according to the new contracts are shown by the arrows on the graph below. However, note that negotiations between Landsvirkjun and Elkem are still ongoing and it is of course possible no agreement will be reached (and then Landsvirkjun would probably be selling the power to other interested companies).

More steps towards rising average power price in Iceland will be taken after 2020, when several old contracts with heavy industries will run out. This applies to a couple of contracts Reykjavík Energy and HS Orka have with the Norðurál smelter (owned by Century Aluminum). This development towards higher power tariffs will probably also affect a very large power contract Landsvirkjun has with the Alcoa aluminum smelter of Fjarðaál, where the tariff is to be re-negotiated no later than 2028 (as can be seen highlighted on the graph at left).

More steps towards rising average power price in Iceland will be taken after 2020, when several old contracts with heavy industries will run out. This applies to a couple of contracts Reykjavík Energy and HS Orka have with the Norðurál smelter (owned by Century Aluminum). This development towards higher power tariffs will probably also affect a very large power contract Landsvirkjun has with the Alcoa aluminum smelter of Fjarðaál, where the tariff is to be re-negotiated no later than 2028 (as can be seen highlighted on the graph at left).

Due to the new contract with RTA in 2010 and some other recent contracts with other smaller power intensive firms in Iceland, the average power tariff in new contracts with heavy industries in Iceland is already rising. This development can be expected to continue, resulting in a general power price to heavy industries in Iceland moving towards approximately 30-35 USD/MWh when transmission cost not included; close to 35-40 USD with the transmission cost. This is shown by the lower green limit on the graph above. Other large customers, i.e. less power-intensive industries and services such as large data centers, will also be experiencing rising tariffs; probably around 40 USD/MWh when transmission cost is not included and close to 45 USD/MWh with transmission cost, as shown by the higher green limit on the graph above.

The development so far is already a clear sign of rising power prices in Iceland. The rising tariffs reflect the necessity to increase return on capital invested in Icelandic power production, which so far has in general been very low, as explained in a recent report by Copenhagen Economics (the slide at left is from a presentation by Copenhagen Economics). Also, rising levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for new power plants in Iceland will push the electricity tariffs up. So rising power prices in Iceland can in fact be explained with simple economics.

The development so far is already a clear sign of rising power prices in Iceland. The rising tariffs reflect the necessity to increase return on capital invested in Icelandic power production, which so far has in general been very low, as explained in a recent report by Copenhagen Economics (the slide at left is from a presentation by Copenhagen Economics). Also, rising levelized cost of energy (LCOE) for new power plants in Iceland will push the electricity tariffs up. So rising power prices in Iceland can in fact be explained with simple economics.