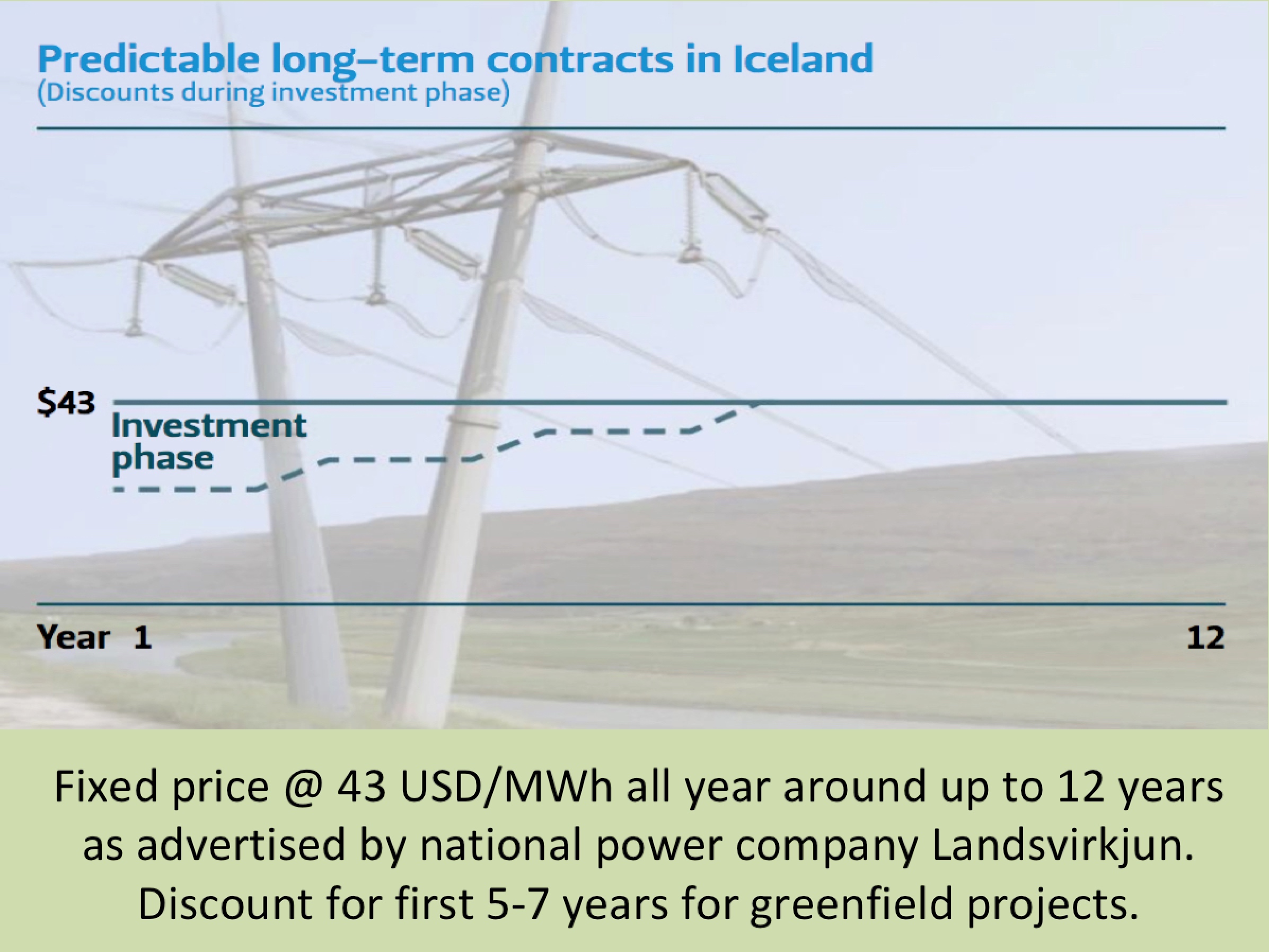

Earlier this month (December 2013), an article in the New York Times told us about the mines of bitcoin that are situated “on the flat lava plain of Reykjanesbær” in Iceland. This article, and several other recent articles in the world’s media about bitcoin, have put a limelight on Iceland’s extremely reliable hydro- and geothermal power. Where companies are offered long time electricity contracts at excellent predictable rates. And the bitcoin mines in Iceland are good example of how Iceland is well situated as a very accessible data storage centre.

Bitcoin is of course the decentralized digital currency and payment network, created few years ago by pseudonymous developer Satoshi Nakamoto. The bitcoin network is based on an open source protocol, which makes use of a public transaction log. A master-list of all bitcoin transactions shows who owns what bitcoins currently and in the past, and is maintained by a decentralized network that verifies and timestamps payments. The operators of this network, known as miners, are rewarded with transaction fees and newly minted bitcoins.

Bitcoin is of course the decentralized digital currency and payment network, created few years ago by pseudonymous developer Satoshi Nakamoto. The bitcoin network is based on an open source protocol, which makes use of a public transaction log. A master-list of all bitcoin transactions shows who owns what bitcoins currently and in the past, and is maintained by a decentralized network that verifies and timestamps payments. The operators of this network, known as miners, are rewarded with transaction fees and newly minted bitcoins.

As more Bitcoin are mined, increasingly greater amounts of computing power, and thus electricity, are required. The fastest miners on the market now sell for thousands of dollars, on top of whatever electricity costs you have to pay to keep what amounts to a supercomputer running 24/7. So how do you keep those costs in check? According to Business Insider you of course pool your resources and move to Iceland.

At the data centre facility in Reykjanesbær in Southwest Iceland, where you can find the Bitcoin mines, more than houndred whirring silver computers are the laborers of the virtual mines where Bitcoins are unearthed. To get there, you pass through a fortified gate and enter a featureless yellow building. After checking in with a guard behind bulletproof glass, you face four more security checkpoints, including a so-called man trap that allows passage only after the door behind you has shut.

The custom-built computers, securely locked cabinet and each cooled by blasts of Arctic air shot up from vents in the floor, are running an open-source Bitcoin program. They perform complex algorithms 24 hours a day. If they come up with the right answers before competitors around the world do, they win a block of 25 new Bitcoins from the virtual currency’s decentralized network. The network is programmed to release 21 million coins eventually. A little more than half are already out in the world, but because the system will release Bitcoins at a progressively slower rate, the work of mining could take more than 100 years.

“What we have here are money-printing machines,” said Emmanuel Abiodun, 31, founder of the company that built the Iceland installation, shouting above the din of the computers. “We cannot risk that anyone will get to them.”

Mr. Abiodun was a computer programmer at HSBC in London when he decided to invest in specialized computers that would carry out constant Bitcoin mining. He is one of a number of entrepreneurs who have rushed, gold-fever style, into large-scale Bitcoin mining operations in just the last few months. These entrepreneurs or digital miners believe that Bitcoin will turn into a new, cheaper way of sending money around the world, leaving behind its current status as a largely speculative commodity.

The computers that do the work eat up so much energy that electricity costs can be the deciding factor in profitability. There are Bitcoin mining installations in Hong Kong and Washington State, among other places, but Mr. Abiodun chose Iceland, where geothermal and hydroelectric energy are plentiful and cheap. And the arctic air is free and piped in to cool the machines, which often overheat when they are pushed to the outer limits of their computing capacity. And Mr. Abiodun prides himself on using renewable power.

In just a few months, that installation has generated more than $4 million worth of Bitcoins, at the current value, according to the company’s account on the public Bitcoin network. He is also expanding his Icelandic operation, shipping in about 66 machines that have been running for the last few months near their manufacturer in Ukraine. Mr. Abiodun said that by February, he hopes to have about 15 percent of the entire computing power of the Bitcoin network, significantly more than any other operation.

Today, all of the machines dedicated to mining Bitcoin have a computing power about 4,500 times the capacity of the United States government’s mightiest supercomputer, the IBM Sequoia, according to calculations done by Michael B. Taylor, a professor at the University of California, San Diego. The computing capacity of the Bitcoin network has grown by around 30,000 percent since the beginning of the year.

Today, all of the machines dedicated to mining Bitcoin have a computing power about 4,500 times the capacity of the United States government’s mightiest supercomputer, the IBM Sequoia, according to calculations done by Michael B. Taylor, a professor at the University of California, San Diego. The computing capacity of the Bitcoin network has grown by around 30,000 percent since the beginning of the year.

Inside the Iceland data center, which also hosts servers for large companies like BMW and is guarded and maintained by the company Verne Global, strapping Icelandic men in black outfits were at work recently setting up the racks for the machines coming from Ukraine. Gazing over his creation, Mr. Abiodun had a look that was somewhere between pride and anxiety, and spoke about the virtues of this Icelandic facility where the power has not gone down once. This is no surprise, as it is a known fact that the Icelandic electricity system is one of the most reliable in the world.

![]() PCC Group is a privately owned industrial holding and participation company based in Duisburg in Germany. The group operates in 16 countries with a total workforce of around 2,800 employees. PCC’s silicon plant in Iceland will be a 32,000 ton facility and is scheduled to start operating in early 2017. It will require 58 MW of power, which will be derived entirely from the renewable energy sources of Icelandic hydro and geothermal power. The contract is subject to certain conditions set to be finalised later this year. These include the appropriate licensing and permit requirements, financing for the project, as well as the approval of the Boards of both parties.

PCC Group is a privately owned industrial holding and participation company based in Duisburg in Germany. The group operates in 16 countries with a total workforce of around 2,800 employees. PCC’s silicon plant in Iceland will be a 32,000 ton facility and is scheduled to start operating in early 2017. It will require 58 MW of power, which will be derived entirely from the renewable energy sources of Icelandic hydro and geothermal power. The contract is subject to certain conditions set to be finalised later this year. These include the appropriate licensing and permit requirements, financing for the project, as well as the approval of the Boards of both parties. Recently, Landsvirkjun was also starting up its newest hydropower station in Iceland. This is the Búðarháls Hydropower Station, and the official start-up ceremony was on March 7th (2014). The Búðarháls Station is Landsvirkjun’s 16th power station and the seventh largest power station owned and operated by Landsvirkjun. This new station utilises the 40 metre head in the Tungnaá River from the tail water of the Hrauneyjafoss Hydropower Station to the Sultartangi Reservoir. The installed capacity of the Búðarháls Hydropower Station is 95 MW and it will generate approximately 585 GWh of electricity per year for the national grid. Most of the electricity added by Búðarháls has already been purchased by long term agreement with Rio Tinto Alcan’s smelter in Straumsvík in Southwestern Iceland.

Recently, Landsvirkjun was also starting up its newest hydropower station in Iceland. This is the Búðarháls Hydropower Station, and the official start-up ceremony was on March 7th (2014). The Búðarháls Station is Landsvirkjun’s 16th power station and the seventh largest power station owned and operated by Landsvirkjun. This new station utilises the 40 metre head in the Tungnaá River from the tail water of the Hrauneyjafoss Hydropower Station to the Sultartangi Reservoir. The installed capacity of the Búðarháls Hydropower Station is 95 MW and it will generate approximately 585 GWh of electricity per year for the national grid. Most of the electricity added by Búðarháls has already been purchased by long term agreement with Rio Tinto Alcan’s smelter in Straumsvík in Southwestern Iceland.