There are several energy companies in Iceland, producing electricity and heating. In total, they generate about 17 TWh of electricity annually and close to 22 TWh of geothermal heat. Almost all this energy comes from renewable sources (hydropower and geothermal power). In total, close to 85% of Iceland’s consumption of primary energy is renewable energy. This is the world’s highest share of renewable energy in any national energy budget.

The largest energy generating firms in Iceland are Landsvirkjun, Orkuveita Reykjavíkur (Reykjavik Energy), and HS Orka. State owned Landsvirkjun is by far the largest, providing approximately 76% of all the electricity produced in Iceland. More than 96% of all hydro generation in Iceland is produced by Landsvirkjun, and its share in the generation of electricity from geothermal power is around 11% of the total.

The largest energy generating firms in Iceland are Landsvirkjun, Orkuveita Reykjavíkur (Reykjavik Energy), and HS Orka. State owned Landsvirkjun is by far the largest, providing approximately 76% of all the electricity produced in Iceland. More than 96% of all hydro generation in Iceland is produced by Landsvirkjun, and its share in the generation of electricity from geothermal power is around 11% of the total.

Landsvirkjun owns eleven hydropower stations and two geothermal power stations with a combined capacity of 1,895 MW. Lansdvirkjun is also the main owner of the Icelandic Transmission System Operator (TSO), with a share of 65%.

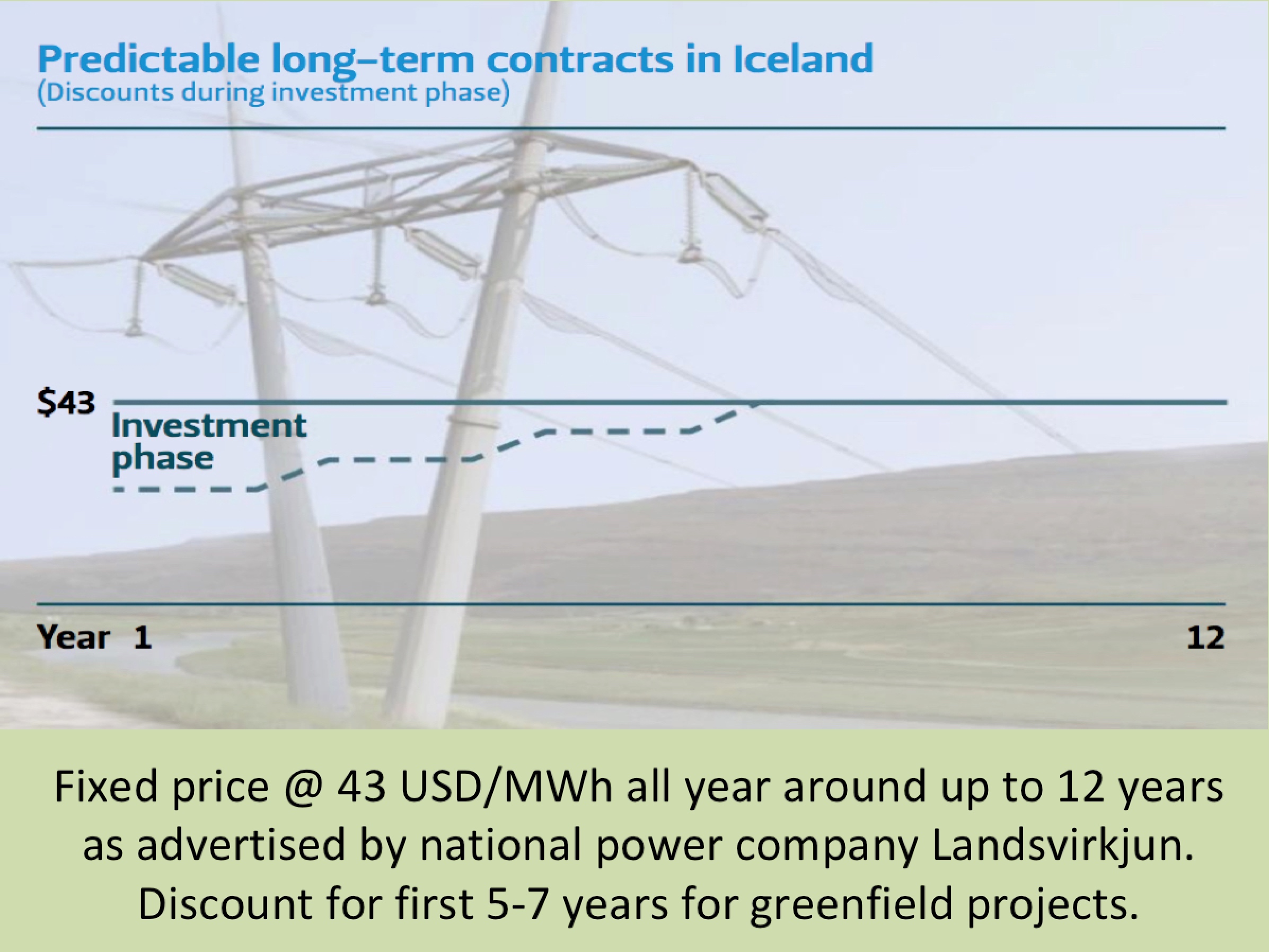

Landsvirkjun receives much of its revenue in foreign currency (USD) as a result of extensive electricity sales to large foreign-owned aluminum smelters in Iceland (80% of the electricity Landsvirkjun generates is sold to energy intensive industries via long term contracts). The economic turbulence Iceland experienced recently did not affect Landsvirkjun nearly as much as most other Icelandic firms (the devaluation of the Icelandic currency did not have negative effects on Landsvirkjun’s income).

Landsvirkjun is one of Iceland’s largest companies and currently it has more equity than any other Icelandic firm . Of all the Icelandic power companies, Landsvirkjun is by far the strongest player and currently the only large Icelandic power company expanding its operations.

Orkuveita Reykjavíkur (OR, but also called Reykjavik Energy) is Iceland’s second largest energy firm. This public utility company provides both electricity and hot water for heating. It is by far the largest local provider of electricity and heating to end-users. The main service area of the company is the larger Reykjavik Metropolitan Area. OR’s largest single customer is Norduaral Aluminum Smelter, that is located not far from Reykjavik. In recent years OR has been struggling with heavy debt, which has led to rising costs for its general customers.

OR’s power-generation plants have a total capacity of 435 MW. Most of the electricity from OR is generated at two geothermal plants that utilize high-pressure steam. Besides producing and distributing electricity, OR sells and distributes both hot and cold water. The water from OR for space heating comes from low-temperature fields in and close to the city and from the combined heat and power plants at the Nesjavellir and Hellisheiði Stations. Cold water is collected from groundwater reservoirs outside of Reykjavík. Also OR operates an extensive sewage system for the Reykjavik area, as well as some adjacent municipalities.

OR’s power-generation plants have a total capacity of 435 MW. Most of the electricity from OR is generated at two geothermal plants that utilize high-pressure steam. Besides producing and distributing electricity, OR sells and distributes both hot and cold water. The water from OR for space heating comes from low-temperature fields in and close to the city and from the combined heat and power plants at the Nesjavellir and Hellisheiði Stations. Cold water is collected from groundwater reservoirs outside of Reykjavík. Also OR operates an extensive sewage system for the Reykjavik area, as well as some adjacent municipalities.

HS Orka is the third main energy firm in Iceland. Until 2007 it was a public company owned by the Icelandic state and municipalities in Southwest Iceland. It was later privatized and today its largest shareholder now is the Canadian Alterra Power. The rest is owned by a group of Icelandic pension funds. HS Orka operates two geothermal power stations with a total capacity of 175 MW. HS Orka owns a few subsidiaries, including ¼ of the well known Blue Lagoon.

According to the news, BMW is moving ten of its high performance computing clusters, consuming 6.31 GWh of energy each year annually, from Germany over to the Verne Global Data Centre in Southwest Iceland. The data centre uses electricity from 100 percent renewable sources – Iceland’s geothermal and hydroelectric generators.

According to the news, BMW is moving ten of its high performance computing clusters, consuming 6.31 GWh of energy each year annually, from Germany over to the Verne Global Data Centre in Southwest Iceland. The data centre uses electricity from 100 percent renewable sources – Iceland’s geothermal and hydroelectric generators.