New low-cost renewable capacity

The main sources of Iceland’s primary energy are hydropower and geothermal power.

86% OF THE TOTAL ENERGY IS GREEN

86% OF THE TOTAL ENERGY IS GREEN

Presently, the Icelandic hydro- and geothermal resources supply close to 100% of Iceland’s consumption of electricity and approximately 86% of Iceland’s total consumption of primary energy (of that total, 20% comes from hydropower- and 66% from geothermal sources). This is the world’s highest share of renewable energy in any national total energy budget.

Hydropower is the main source of the country’s electricity production, accounting for approximately three-quarters of all electricity generated and consumed. The remaining quarter is generated in geothermal power stations.

GEOTHERMAL DIVERSITY

Although hydropower is the main source for Iceland’s electricity production, geothermal heat is the main energy source in Iceland. As mentioned above, geothermal energy makes up around 66% of all primary energy use in the country.

The principal use of geothermal energy is space heating. Close to 90% of all energy used for house heating comes from geothermal resources, thanks to the country’s geophysical conditions and extensive district heating system. Geothermal energy also plays an important role in fulfilling an increasing electricity demand. Other sectors utilizing geothermal energy directly include swimming pools, snow and ice management, greenhouses, fish farming, and industrial uses.

STRONG GROWTH AHEAD

It is expected that demand for Icelandic renewable electricity will grow quite fast over the next few years. Iceland’s main power company, Landsvirkjun, has introduced plans for increasing its electricity production up to 75% within a decade.

The fact that Iceland still has numerous very competitive unharnessed hydro- and geothermal options, makes the country an interesting location for all kinds of energy intensive industries and services. This may for example apply to data centers, aluminum foils production, several silicon production facilities etc.

The abundant natural hydro- and high temperature geothermal resources make the Icelandic power industry able to offer electricity at substantially lower prices than for example can be found in any other European country. Even the present low spot-price for electricity in the USA (due to extremely low price of natural gas) are no threat to the Icelandic electricity industry.

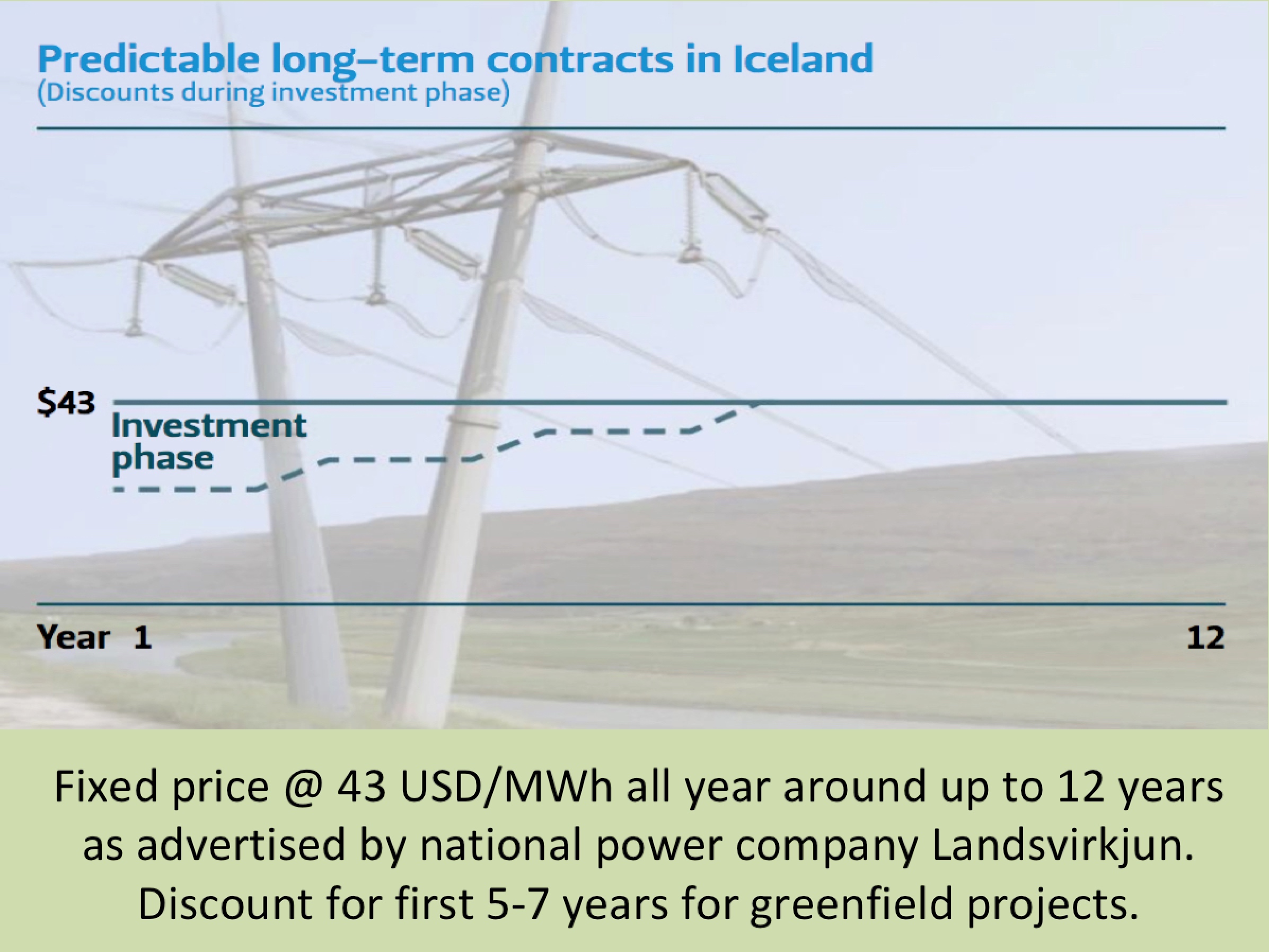

Companies that need substantial quantity of electricity and wish to operate within the OECD / Europe, will hardly find better long-term agreements than offered at the Icelandic market (43 USD/MWh in 12 year contracts are being offered by Landsvirkjun).

In addition to attractive electricity contracts, Iceland is a member of the European Economic Area and has a modern business environment based on European standards. For those considering energy-related investments in Iceland, a positive first step is contacting Icelandic professionals on the relevant subjects. At Askja Energy Partners we provide information and access to the most experienced and knowledgeable engineering, legal, tax, and accounting services.